Daughters of Darkness and the psychedelic collision of gender and exploitation

Lesbian vampires never hit so hard

Trying to drill down to the core of the lesbian vampire trope would be a struggle of Greek proportions. Put mildly, it is a layered subject that I’m not sure that I have the experience nor the desire to address. But I do find it fascinating. Looking beyond the primary motives of male fantasy, it’s a ubiquitous trope that remains largely unchanged from its origins in Joseph le Fanu’s story, Carmilla, in spite of the shifting sands of vampire symbology. It’s tempting to simply chalk it up to simple titillation. Sexual arousal is hardly a simple thing, however, and from their beginnings in published fiction, vampires are inextricably linked with sexuality and death. Polidori’s The Vampyre is about a vampire who goes around seducing women before killing them. Carmilla is about a young girl and her budding sapphic romance with a mysterious girl who turns out to be an ageless vampire. Dracula is well-known for its themes of domination and submission. A few years after Tod Browning’s original Dracula was released, Universal gave us Dracula’s Daughter, with its chaste but present themes of a gay vampire and it seemed to light a fire in the people who would go on to make future experiments in vampire media. The fantasy of vampirism has much more going on than immortality and ageless beauty. It’s a license to give yourself over to your worst animal impulses. Untethered from mortal obligations of morality, you live forever, doing whatever the hell it is that you want to do and based on the common themes of vampire fiction, writers assume that everyone wants to eat and fuck.

They’ve been done in varying shades of good and bad. The earliest example is typically traced back to 1936’s sequel to Dracula, Dracula’s Daughter but in these earliest incarnations of the trope, the queerness was treated predictably. Homosexuality was treated as a frailty of spirit and the women in these movies were predatory as a result of their choice to be gay, hunting other women to draw them into their shadowy world of the night. Vampires in this context are a force of corruption, set to draw women away from their static place in society: the home. They become unavailable to the men of the straight world who need them to be their caretaker, mother, and sexual outlet. The threat at play in these movies is a woman’s agency. The vampire fantasy takes on a quality of freedom that’s threatening to the male hegemony. It’s no wonder that the lesbian vampire trope hasn’t changed much while the vampire metaphor, overall, continues to transform with the times. Men will always feel threatened by a woman acting of her own accord.

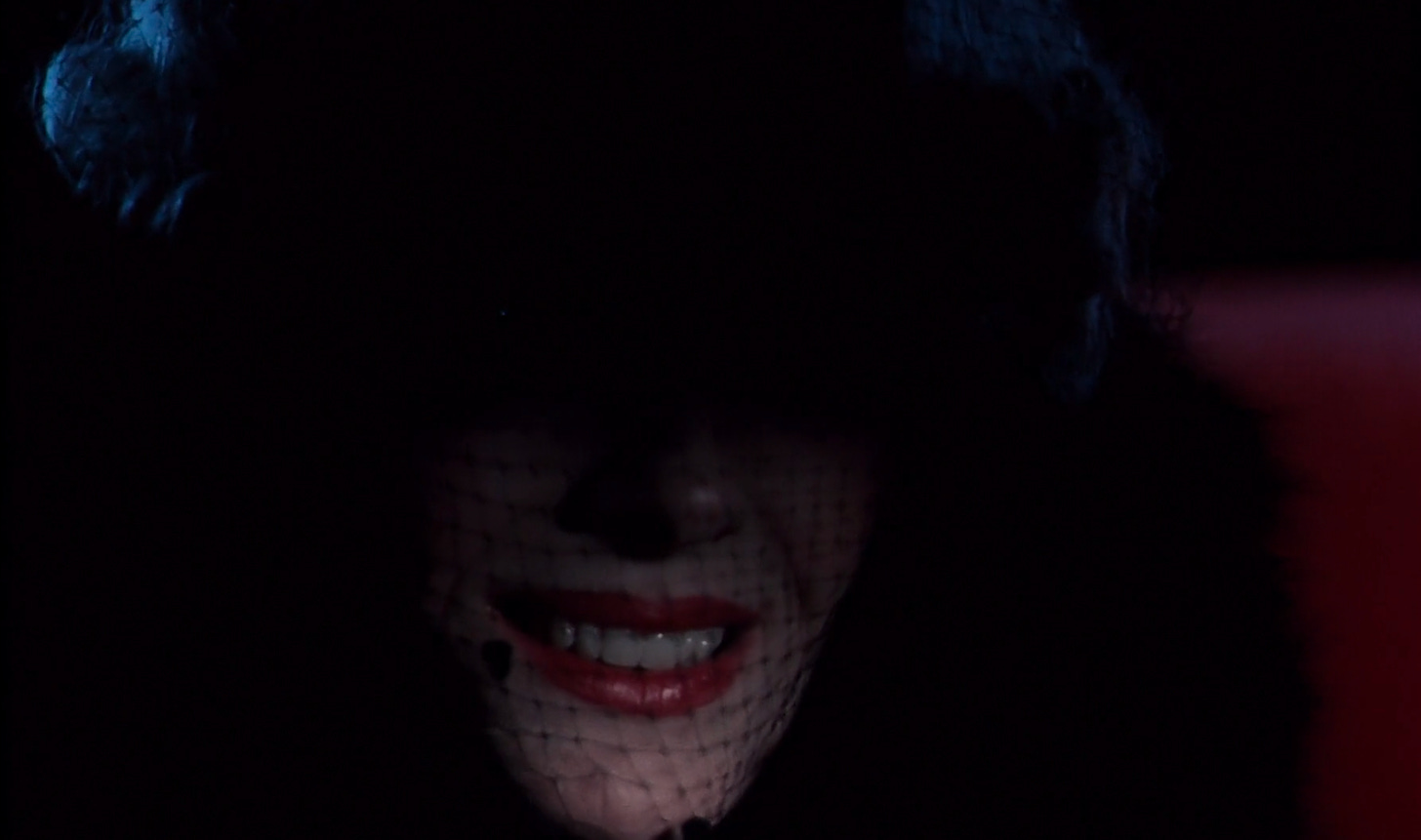

Almost simultaneously, Hammer released The Vampire Lovers, Jess Franco released Vampyros Lesbos, and Jean Rollin began his signature series of gauzy fever dreams with Rape of the Vampire. The lesbian vampire trope as we know it formally took flight. At the end of the day, though, the motivating factor for these productions was base eroticism. The movies that followed never offered much more than sexy tableaus. However, as the major players were laying the foundation for their lesbian vampire cottage industries a movie came along and snuck through with an interesting dimension. Harry Kumel submitted Daughters of Darkness to the public with an emphasis on art, with one foot in the French New Wave. A Belgian and French co-production, Daughters of Darkness stands out from the crowd in significant ways. Though, it occupies the same territory of other exploitative vampire movies, it feels like something else, entirely. Hammer’s movies were made with the same level of competence that you could expect from their films. They were shot on the same sets as had the same level of gothic grandiosity as the rest but were ultimately schlocky monster movies at heart. Franco’s movies had the same degree of suitable sleaze as the rest and he approached the vampire mythology with casual disregard if it impeded his intentions to film Soledad Miranda in a bikini. Rollin’s low budget oddities come close to what Daughters of Darkness was working on but his budget limitations meant that he had to cast models and porn actresses which necessitated strict limitations on dialog and drama, relying instead on a heady gothic atmosphere. Kumel did not have this problem. He came to the party with Delphine Seyrig whose reputation connected her to some of France’s most iconic directors of the time. The product is equal parts trashy horror movie and French New Wave and it’s great!

The film is about a couple sharing space with a mysterious stranger at an empty hotel in Belgium and it strikes hard at notions of gender roles and a woman’s agency. We begin with claustrophobic shots of our main couple having sex in a train car. We never learn much about them and we certainly don’t know how they met but what does emerge are clues that suggest that these two don’t really know each other much at all. Their marriage seems to be an impulsive, spur of the moment Vegas-style wedding. For all intents and purposes, Valerie is a blank slate. Her newlywed husband, Stefan, however, has baggage. They check into a baroque old hotel in the coastal city of Ostend and find that they’re the only ones there since it’s winter in Belgium and not a terribly suitable season for coastal tourism. But what’s this? A beautiful stranger arrives in the middle of the night with her young companion and the two couples begin a dance that ends with murder, freedom, and the symbolic obliteration of male dominance.

Daughters of Darkness lives in the shadow of the broader vampire current but you can see its significant influence on several movies that followed. Rollin, himself, seems to have taken a page from the proceedings when he made the movie Fascination and Tony Scott’s crucial vampire flick, The Hunger, bears more than a passing similarity. The cast in each of these films is primarily made up of women struggling against the gravity of a man but Daughters of Darkness seems to be the only one specifically operating with an agenda.

Gender stands at the center of the movie. It’s the entire operating principle. Stefan, as the film’s lone male character of consequence, regards Valerie as a thing to be owned or mastered. Through the first half of the movie, the matter of Stefan’s mother looms heavily over everything. He is uncomfortable at the very mention of her. He bribes the man at the hotel’s desk to aid him in his avoidance of his mother. It’s inevitable that we meet her and the movie goes to great lengths to build her up as this massive antagonistic force. When Valerie and Stefan have sex, he puts a great deal of emphasis on her breasts. The character of his sexual performance is desperation. Suddenly leaping into marriage with a woman he hardly knows speaks to his insecurity around his own concept of male gender roles. Prior to the phone call to Mother, Seyrig’s Elizabeth Bathory and Stefan engage in a bizarre scene where she has him recount to Valerie the nature of the real Bathory’s crimes. Each one is a description of a penetrating attack and each description drives the pair deeper into frenzied arousal. When Stefan’s mother is finally introduced, we find out what all the fuss is about. She symbolically castrates him in a brief, minutes-long conversation that turns the entire movie on its head. Where it was perfectly reasonable to see Stefan’s taking of Valerie before as an act of owning her, it now seems that the ownership isn’t of a person but is the very ownership of femininity, itself. As this all plays out, Bathory puts her own machinery in motion to twist the knife when she sends her companion, Ilona, to seduce Stefan and Ilona denies him her breasts and symbolically takes the dominant position by being on top of him. Her accidental death following the sex scene ends up being the straw that breaks the camel’s back and he is rendered utterly useless to the surviving women. Throughout the film there are numerous tracking shots which linger on hands. They’re a powerful symbol for doing, for action. We take with our hands. We manipulate. Is it any wonder that when Stefan meets his final fate, the women drain him from the open wounds at his wrists?

All the while, Bathory engages in a sustained campaign to draw Valerie away from her husband who starts off the movie as utterly insufferable, gets pretty weird and ends in a foul, abusive place. The vampire myth offers Valerie a liberation that living as a mortal woman cannot afford her. She can be mastered or she can be the master. But the choice isn’t as simple as it seems. Seyrig’s performance as Bathory is camp of the highest order. Her embodiment of a powerful vampire is that of a classic Hollywood movie star and you really want to see her come out on top since she’s so charismatic and commanding but you do have to bear in mind that she’s a wicked creature and the likely killer of the young women who drop like flies in Ostend around the time of her arrival. Bathory’s liberating kiss isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be, either. Though, she presents a particularly freeing case to Valerie, her treatment of Ilona isn’t all that different from Stefan’s treatment of Valerie. This dynamic and conflict is what ultimately takes a good ending and makes it great.

Daughters of Darkness is the definition of a sleeper hit. It’s a shame that so few people have seen it as it is positively jam-packed with goodness. It works perfectly, solely as a piece of vampire sexploitation but thoughtful viewers will find endless code and symbolism to ruminate on. While it’s certainly not a progressive movie by the expectations of a modern viewer, it was certainly way aheads of its time in the way that it presents and criticizes gender roles and class structure at a time when the second wave of feminism was only starting to gain steam. You’re doing yourself a favor by watching it.