The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and the horror of fairy tales

Fairy tales are inherently awful to their core

A decade seems like a long time but the older I get, I look back on my life and realize that ten years ain’t shit. It passes before you know it. So, by the time that 1983 rolled around and my family drove out to some electronics store on the edge of Boston to buy our first VCR, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre had been out for ten years, making the rounds at drive-ins and midnight movies and it had been available for video rental through Wizard Video for only a year. For many, Texas Chainsaw was only a lurid spectacle, notorious by reputation, alone, but rarely seen by upstanding members of your community. As a little kid with a fascination for the forbidden shelves of the horror section at Video Paradise in Salem, no fruit was more forbidden, nor more attractive. You could only speculate at what lay on the electromagnetic signal of the tape. If my mother was to be believed, it was the most cruel, most gory affair and how could I doubt her? The Wizard Video box kept it simple, placing the picture’s theatrical poster in black and white, tinted in red, on a red box. A man with a fucked up face, bearing a chainsaw faced the world while a woman hung on a meathook struggled for escape. Everyone I spoke to assured me that it was every bit as awful as my imagination conjured. Hardly anyone had seen the movie across its first ten years of life. No one could tell you what the movie was about. Across ten years of silence that movie built up a reputation based on speculation, alone.

Years later, Cinemax ran Friday the 13th. I popped in a blank tape, hit record and watched the movie until I fell asleep. Because I was recording on EP mode, I ended up with the rest of the tape full when I woke up. Friday part 1 was followed by Friday part 2 and then The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Finally!

Imagine my disappointment.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre may not be the gory splatter gauntlet that the adults in my life made it out to be but it’s still a god damn nightmare. It just took a long time for it dawn on me. When you’re a kid and your expectations are as high as high can be, to be let down is devastating. You don’t have the mental equipment yet to accept that life is full of swerves and that adults don’t know shit. It took many repeat viewings and age for me to come around to it and while it may not be a favorite of mine, I have no problem placing it among the contenders for greatest horror movie of all time. Among those repeat viewings, some of them coinciding with a study of folklore, I came around to a strange revelation: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a pastiche of fairy tales.

Fairy tales are horrifying by their very nature. They make great public domain fodder for anyone looking to adapt something child-friendly to a new animated picture and as a result, the modern understanding of them tends to be pretty sterile and lyrical but in their original incarnations, fairy tales are the horror stories of yore. Many of them bear a moral at the end, usually an admonishment not to stray into places predatory or unpredictable. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is one such fairy tale with a few twists.

In most (but certainly not all) fairy tales there’s a definite boundary between the realms of the real and unreal typically represented by The Path or The Forest. Staying on the path implied safety. Even though it may be bordered by the wilds on either side, the path was a safe zone for ordinary mortals. It was clearly cut through the wildlands and no harm could come to you as long as you maintained your course on the straight and narrow. Peril came to those who strayed or were tempted away. The Forest represented a similar threat but in the stories where our protagonists submit to its embrace, The Forest represents a challenge that must be met in some other place. Entering into The Forest, even with a weapon, suddenly places you a little further down the food chain and our status as apex predators of the settled world is invalidated. The Forest might also represent a shift of setting, as well. Leaving the ordinary human world and entering into a more enchanted but no less perilous world of spirits and Fair Folk.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre begins right on the edge of The Forest as rural Texas is introduced as a frontier of insanity and degeneracy. The area’s cemeteries are the scenes of terrible desecrations and grave robbing. Sally, her wheelchair-bound brother Franklin, and friends arrive to one of these cemeteries to check on their grandfather’s grave. In this place we’re already in Little Red Riding Hood territory, replacing a sick grandmother with the potentially desecrated grave of grandfather. Unable to find it, Sally and friends continue on, eventually picking up The Wolf as a deeply distrubed hitchhiker who first terrorizes the group of friends and then performs a series of acts which could be seen as magical or ritual: he cuts his own hand with Franklin’s knife, takes and then burns a photo of the friends, cuts Franklin’s arm, and then smears his blood on the side of the van as they leave, leaving behind a smear that, while having no actual occult purpose, appears quite occult and preoccupies Franklin. Before and after these scenes Sally’s friend Pam enlightens the group on matters of astrology, implying prescience of things to come.

The Wolf represents both temptation and danger in fairy tales. He is often portrayed as anthropomorphic, either having human and wolf characteristics, like a werewolf, or having the appearance of a wolf but the mannerisms and wit of a human being. He is both parts upright and charming as well as dangerous and lethal. He’s the familiar, replaced by the uncertain. Here, in Texas, The Wolf is represented by two people. The dangerous and uncertain is represented by The Hitchhiker. He’s our protagonists’ first brush the approaching wilds of The Forest. He’s the signal that they’re leaving regular space and entering into a treacherous wildland. The more human side of The Wolf, the deceptive and upright version, comes up the road a bit at the gas station as they meet The Old Man who scopes them, recognizes the mark on the van, and insinuates himself into their experience in The Forest as someone they can trust as things become threatening. And while he may not be trustworthy in a more meaningful sense, our direct experience with the people on the borders of the unreal up to this point have been a manic hitchhiker and a man, blind drunk, rolling around on the ground at a cemetery. Friends in this space are hard to come by. He offers them a bit of pushback about going out to the houses in the area but The Wolf eventually helps them find Sally’s childhood home, grandfather’s house, and deceptively sells them barbecue made from human meat.

At this point in the story, the tale shifts from Red Riding Hood to Hansel and Gretyl. The van is low on gas and the protagonists need to hold over until the morning to buy more. They’re lost in the wild, low on gas, and looking for a house which they find in a state of terrible disrepair, consumed by The Forest.

It’s here that The Path finally emerges. Grandfather’s house offers a brief shelter but there’s a lot of time to kill and not much to do except visit a nearby creek which Franklin points out is at the end of a trail between two sheds behind the house. The Path here is safety but, like in Hansel and Gretyl, a nearby house, situated off of The Path, offers temptation to Jerry and Pam. A generator runs there, implying that there may be some gas that our protagonists can buy in order to return back to the world of the normal. They leave the path, just as Hansel and Gretyl did, and encounter The Witch/The Ogre/The Giant, in the form of Leatherface who, just like The Witch in Hansel and Gretyl, is a cannibal and both are horribly dispatched by hammer and hung on a meathook, to be thrown into the oven at a later time.

In the midst of this, Pam, looking for Jerry, enters the house and encounters The Locked Room of Bluebeard fame. The House, not terribly inviting even from the outside turns out to be every bit the charnel house of Bluebeard’s dungeon as she makes a horrible discovery: The room is literally full of bones and teeth, some of them fashioned into furnishings. And just like Bluebeard’s bride she is seized, here by the The Witch, and hung on a hook to die like the rest

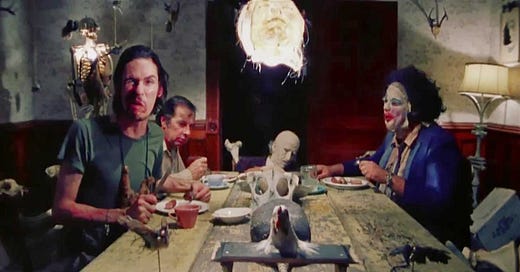

The Path, The House, and The Witch whittle the party down until only Sally and Franklin remain, a better model of Hansel and Gretyl than the rest of the cast and the story shifts gears to a model closer to Jack and The Beanstalk, as Leatherface using the movie’s analog for The Axe, a chainsaw, murders Franklin and chases Sally until she reaches the gas station where The Wolf shows his true form, stuffs her into a bag (such is often found in folktales of “Gypsy Witches” or even The Krampus, stealing naughty children away in a sack) and takes her deep into the film’s deeply disturbing third act. Sally is now deep inside Arcadia, the land of the fair folk.

Like fairy tales, the modern world has stripped the eponymous fairies of their danger, instead replacing them with pastel colored pixies for a more comfortable consumption among children and the new age set but fairies, based on actual fairy lore, are fucking ineffable and terrifying. To go to their world and partake of the things there traps you in their world forever. They’re always stealing children and replacing them with something that looks like the child, but isn’t, known as a Changeling. In this case, The Wolf lures Sally off the path and just as she’s about to get away, he steals her away and subjects her to the rules of Arcadia, which twists and breaks her sanity. Sally, the only survivor, who runs from The House as The Giant chases her with The Axe, returns to the path, represented by a nearby road, where she is rescued, but what returns from Arcadia is not the same Sally that went in. She’s been screaming almost nonstop for the last thirty minutes, and as she escapes from Leatherface, who flails in the rising sun in frustration, she laughs.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre may not be the nonstop splashy gorefest that I always assumed that it is, but it’s an absolute gauntlet of terror from start to finish. Tales of the production are chock full of horror stories of production amidst a wicked Texas summer and this quality shines through in every scene. The House is claustrophobic, squalid and full of bones and teeth. Dusty and dry is something somehow far worse here than sets smeared with fake blood. The exterior shots appear to be dusty and stifling hot and when you add this fairy tale layer to it, there’s a Through The Looking Glass quality about it that furthers the insanity by distorting everything like a funhouse mirror in a shitty carnival.

I may have been letdown when I first saw The Texas Chainsaw Massacre but it only gets better with repeat viewings and the older I get, the more awful shit I see in it.

This one I came to late, long after I’d seen enough teen slashers to know I generally loathe them—in my opinion they fake at being counterculture, when they are morality tales in different garb—and it disturbed me, as it is like you said, a fairy tale for the post-Manson/Ed Gein world. It seemed beyond morality, except for the general “don’t stray from the path” narrative that has been in our tales since the beginning. I can see the door slam shut behind Leatherface as he drags a body into the abattoir even now, and I’ve watch it exactly once. You say it well, it is a story of archetypes and works on that level, the deepest one, with its grimy facade of gore masking the fairy tale colors of the forest, the red cape, the wolf’s grizzled mane.